This article originally appeared on Newsroom

Moving large portions or even whole populations of low-lying states in the Pacific is a long-term enterprise that could go wrong if New Zealand doesn’t engage with it fully.

Climate Change Minister James Shaw and Pacific Peoples Minister Aupito Su’a William Sio have given strong statements about supporting climate migration from Kiribati and Tuvalu. They signalled something more sophisticated than simple migration, and innovation will be needed.

There are 114,000 I-Kiribati and only 11,000 Tuvaluans. New Zealand’s net immigration is around 70,000 people annually. Even though this may come down with the new government, the numbers of climate migrants under consideration are not significant, especially if relocation is done over years or even decades.

But while the numbers may be small for New Zealand, the move is significant for I-Kiribati and Tuvaluans.

The concerns about climate migration relate to transforming from being members of outright majorities in their home countries to members of small minorities elsewhere, especially if communities are fragmented throughout the region. Relocation could threaten the social fabric that enables I-Kiribati and Tuvaluans to manifest their national identities through culture, language, norms, customs, and so forth.

On its own, therefore, simple migration threatens their ways of life: te katei ni Kiribati and tuu mo aganu Tuvalu.

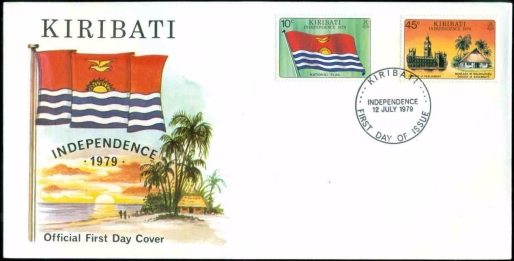

Kiribati (1979) and Tuvalu (1978) were among the last Commonwealth states to recover their independence from the UK, and but again their existence as nations and peoples is threatened by exogenous forces.

To deal with Pacific climate migration, Shaw signalled interest in the Nansen Initiative Protection Agenda. This is a voluntary framework for states to protect peoples who move across borders to escape sudden-onset disasters, like cyclones, and slow-onset disasters, like sea-level rise.

The Protection Agenda contains a number of recommendations. First, states need to collect data. They need to know which areas and communities are most at risk, and collaborate on developing scenarios for when and how cross-border relocation might occur.

Destination states, like New Zealand, also need to review their legal frameworks for managing incoming peoples: can existing visa schemes be adapted, or can visa requirements be waived altogether? Shaw is looking at developing an experimental humanitarian visa. Also, since returning to low-lying states will get more difficult and perhaps impossible, can the requirements for permanent residency and/or (dual) citizenship be simplified?

The Protection Agenda also recommends destination states provide assistance with basics: shelter, food, medical care, education, livelihoods, security, family unity, and respect for social and cultural identity.

For long-term settlers, measures to support sustained cultural and familial ties are recommended, along with recovery and reconstruction assistance.

The Protection Agenda is designed to be adapted for particular situations. What, then, are the local issues New Zealand, Kiribati and Tuvalu need to address?

Internationally, most cross-border displacement involves only a small part of a country’s population, but for Kiribati and Tuvalu climate change could require most or even entire populations moving permanently, and this has different implications.

Sio recognises low-lying islanders’ concerns about loss of national identity and suggests legislative protection for I-Kiribati and Tuvaluan languages.

But there is a broader issue, relevant in international law, but frequently overlooked in climate migration talks: the right to self-determination.

Self-determination is more than “migration with dignity” or being consulted.

According to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which New Zealand ratified in 1978, self-determination is an inalienable, collective right of peoples to freely determine their political status and to freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.

Climate migration risks self-determination in two important ways. First, communities may be fragmented: some move to Auckland, some to Suva, some to Brisbane. Second, communities transform from outright majority to small minority.

No matter how well-intentioned, if climate migration allows these things to happen, the result is the peoples’ right to self-determination will be undermined.

New Zealanders know well that depriving peoples, like iwi and hapū, of their enjoyment of self-determination is catastrophic.

Being forced to move to New Zealand might end up as a kind of inverse colonisation: instead of the coloniser coming to peoples and forcing them to assimilate the coloniser’s culture, peoples now have to come to another society and integrate into that society’s culture.

While cultures are not static phenomena, and the peoples will enjoy some measure of protection of their culture, within a couple of generations the changes for migrant I-Kiribati and Tuvaluans in a new, dominant culture will be profound.

In the short term, rescue and protection is the fundamental requirement, and that’s where New Zealand will likely start. But, working with I-Kiribati and Tuvaluan as equals, New Zealand must recognise these peoples’ inalienable right to self-determination.

We need to recognise, too, that te katei ni Kiribati and tuu mo aganu Tuvalu are different ways of life to Pākehā’s ‘Homo economicus’ modus operandi, and also need to be enabled.

Long term, as well as providing humanitarian visas, we can work with the low-lying states on innovations to determine:

- How Pacific islanders might own land (whether individually, or in common; perhaps in a form similar to Māori Freehold Land)

- The type of legal person that represents their communities in New Zealand (like a trust or a corporation) and internationally (how their states continue or change into some other international legal personality)

- How to enable cultural norms and practices, language, and national identity

- Whether these countries can access global climate change adaptation funding to buy land and otherwise re-establish communities here in New Zealand

- Whether we have another system of laws and norms – along with common law and Māori custom – and, if so, how that might work.

If New Zealand and the global community reduce greenhouse gases urgently and fund in situ adaptation, these innovations should be unnecessary.

But if migration becomes necessary for low-lying states and New Zealand wants to help, we have to do so in ways that are socially and culturally sustainable.